Everything you need to know about mould and mycotoxins

What comes to mind when you think of mould? Maybe it’s the neglected loaf in the breadbin that’s developed a furry blue coat, or perhaps it’s the memory of the damp walls of your scruffy old student digs. But you might not naturally link it with the litany of mental and physical health complaints that mould exposure can cause or exacerbate.

Living in Cornwall, we know a thing or two about damp conditions. The same sea air that is so invigorating on coastal walks can wreak havoc when trapped inside a poorly ventilated cottage. But this familiarity with mould also means it’s a nemesis we have experience in tackling – helping our clients mitigate the effects of mould exposure and successfully treat problem damp patches in their homes.

What exactly is mould?

Mould is a collective term used to describe over 100,000 species of naturally-occurring microscopic fungi.[1] Mould is all around us – indoors, outdoors, and floating invisibly in the air. It is an essential part of the ecosystem that helps break down organic matter.

Mould spores make their way into buildings through open doors, windows and vents – or even by hitching a ride on your clothes or pets. Once inside, they thrive in the presence of moisture and a food source (such as paper or fabric). Mould spreads by releasing spores into the air in search of other suitable surfaces to colonise.[2] “All it takes is 24 to 48 hours for a mould spore to put down roots and spread,” explains author of The Mold Medic, Michael Rubino.[3]

Not all mould species are toxic – some add flavour to foods while others are perfectly innocuous, but most of the moulds you spot inside your home are bad news for your health.

What about mycotoxins, what are they?

Some moulds produce toxic microscopic particles called mycotoxins. Think of them as the self-defence mechanism of mould; when the mould is disturbed or feels threatened, it will release mycotoxins to protect itself and allow its spores to spread further. Though odourless and invisible to the naked eye, mycotoxins can cause illness, allergy and disease in humans and animals.[4]

“The term mycotoxin was coined in 1962 in the aftermath of an unusual veterinary crisis near London, during which approximately 100,000 turkeys died,” explains Alex Manos,[5] a leading Functional Medicine practitioner specialising in mould illness. “When this mysterious turkey disease was linked to a peanut meal contaminated with secondary metabolites from the fungus Aspergillus flavus (which produces the mycotoxin aflatoxins), it alerted scientists to the possibility that other mould metabolites might be deadly.”

“Some 300 to 400 compounds are now recognised as mycotoxins, of which approximately a dozen groups regularly receive attention as threats to human and animal health,” says Alex.

Mycotoxins are also lipophilic, meaning they dissolve in fat. So, from body fat to cell membranes, we can unknowingly store harmful mycotoxins in our fatty tissues.[6]

What causes mould?

Mould is caused by excess moisture. Inside a building, this moisture might be due to leaking pipes or guttering, water-damaged walls, windows, doors and roofs, or rising damp in basements and ground floors. Or, it could be from poor ventilation, a lack of insulation, or a build-up of condensation.

And while you might associate humidity with hot and sticky climates, it's surprisingly common in the UK's colder, wetter months. In London, for example, humidity levels regularly reach 80% in autumn. Black mould can grow at any level above 55%.

Our daily activities help contribute to mould growth, too. Thanks to our double-glazed windows, airtight new builds, and steam-producing habits – think showering, drying clothes, cooking, mould thrives inside modern homes.

Types of mould to look out for

Mould species fall into three main categories depending on the moisture level required for their growth. Some of the most common household species are listed below, but true identification can only be achieved with laboratory help.

Primary Colonisers:

These are xerophilic spores, meaning they require very little to no moisture to colonise a surface. Most sub-species in this group begin with the Latin name Aspergillus or Penicillium, such as the well-known Aspergillus Candidus. Easily identified as white and fluffy rounds, this is just one of many xerophilic moulds that can grow on carpets, curtains and other furnishings. Xerophilic spores are also commonly found in foods like grains and fruit. These spores are so dry even a draft can disperse them into the air. Once inhaled into the airways and lungs, they can cause allergic reaction, irritation of the air passage and even widespread fungal infection in immunosuppressed individuals.

Secondary Colonisers:

These are the middle ground in terms of moisture requirement for growth, and a common sub-species found in homes is Aspergillus Versicolor. Although characterised by a musty odour, it can be tricky to detect due to its colour variation with maturity, from milky yellow to pale green or even pink. Unfortunately, it’s also one of the most hazardous moulds, releasing the carcinogenic mycotoxin Sterigmatocystin, which has been linked to kidney and liver cancer in animals.[7]

Tertiary Colonisers:

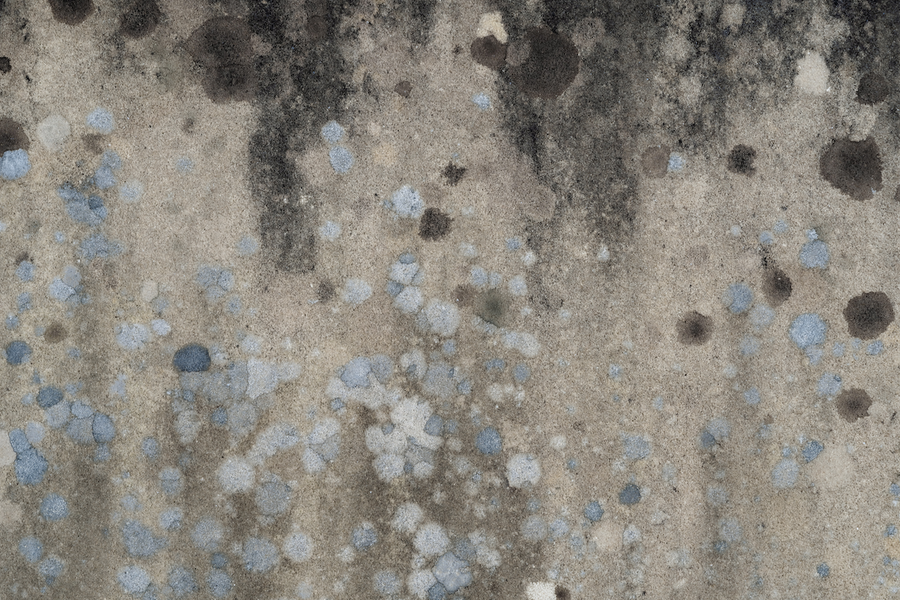

These types of mould are hydrophilic, meaning they thrive on moist surfaces like windows and walls directly behind furniture. Moisture content of above 90% is ideal, so pay close attention to areas where condensation builds up. Black mould (Stachybotrys Chartarum) is a highly toxic hydrophilic mould, often found in attics or particularly cold houses. Its appearance ranges from tiny black dots to larger clusters. The release of S. Chartarum mycotoxins called trichothecenes was linked to a case of acute pulmonary haemorrhage in 10 exposed infants at a hospital in 1994 - a condition which can be fatal.[8]

How to spot mould and damp at home

The key areas to look out for signs of mould growth in your house include:

- Around sinks

- On shower curtains

- Around the bathtub and shower fittings

- On curtains

- In basements

- Behind furniture

- On the back of picture frames

- On bathroom and kitchen tiles

- Behind wallpaper

- Under window sills

- Around window frames

- Inside cupboards

- On plumbing

- On damp walls and ceilings

In really damp houses, mould can grow visibly on clothes, shoes, carpets and soft furnishings.

How to test for mould at home

For a simple way to check your home for mould that takes less than a minute, Mindbodygreen suggests opening up the cover of your toilet tank and checking the undersides. If there’s mould in there, it could mean that you have mould elsewhere in your house that’s providing the spores needed to start growing inside your toilet tank.[9]

Or why not try the Micro Balance Mould Screening Test Kit, which is available to purchase in the Conscious Spaces Shop? Testing takes minutes, and will provide accurate results in just 5 days that will help reveal whether the mould in your space might be reaching unhealthy levels with allergy and disease implications.

But mould growth isn’t always easy to spot: it can hide from view behind walls, in vents or under floors – invisibly polluting the air you breathe. And, it can have a significant impact on your health, as we reveal in our next article...

References

[1] https://science.howstuffworks.com/life/cellular-microscopic/black-mold.htm

[2] https://www.cdc.gov/mold/default.htm

[3] https://www.mindbodygreen.com/articles/air-circulation-in-bathroom-to-prevent-mold

[4] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC164220/

[5] https://www.alexmanos.co.uk/mycotoxins/

[6] https://uk-podcasts.co.uk/podcast/cpress-state-of-mind/could-mould-allergy-be-the-missing-piece-of-your-h

[7] https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29842907/

[8] https://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0017/43325/E92645.pdf

[9] https://www.mindbodygreen.com/articles/quick-test-for-seeing-whether-your-home-has-mold